Safety should be an unwritten rule, a social norm, that workers follow regardless of the situation. It should become a value that is never questioned—never compromised.

It is human nature to shift priorities, or behavioral hierarchies, according to situational demands or contingencies. But values remain constant. The early morning anecdote illustrates that the activity of “getting dressed” is a value that is never dropped from the routine. Should “working safely” not hold the same status as “getting dressed”? Safe work practices should occur regardless of the demands of a particular day.

Safety should be a value linked with every activity or priority in a work routine. Safe work should be the enduring norm, whether the current focus is on quantity, quality, or cost-effectiveness as the “number one priority.” The ultimate aim of a Total Safety Culture is to make safety an integral aspect of all performance, regardless of the task. Safety should be more than the behaviors of “using personal protective equipment,” more than “locking out power,” “checking equipment for potential hazards,” and more than “practicing good housekeeping.”

Safety should be an unwritten rule, a social norm, that workers follow regardless of the situation. It should become a value that is never questioned—never compromised.

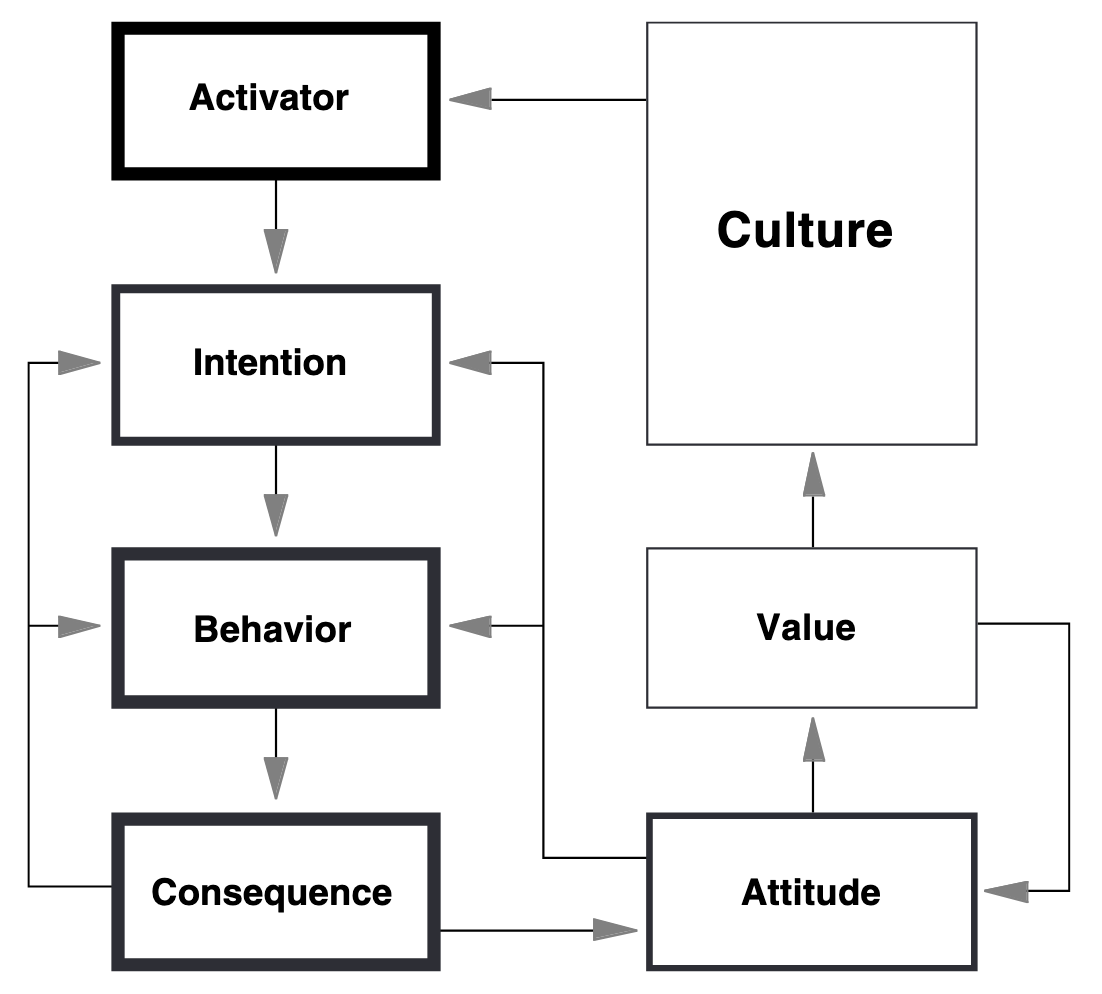

This, of course, is much easier said than done. How do you even begin to work for such lofty aims? Figure 3.9 summarizes the relationships between intentions, behaviors, attitudes, and values. It outlines a starting point and general process for developing safety as a corporate value. A key point is that attitudes and values follow from behavior. This brings us to behavior management techniques. They are the starting point for acting a person into safe thinking.

This is how it works. When you follow safe procedures consistently for every job and attribute your behavior to a voluntary decision, you begin thinking safely. Eventually, working safely becomes part of your value system.

Figure 3.9 illustrates how attitudes and values influence intentions and behaviors directly. However, as discussed in Chapter 2, it is not cost-effective to manage attitudes and values directly to “think people into safe acting.” Notice in the figure the different thicknesses of rectangles enclosing the terms. The thicker the border, the more measurable and manageable the concept. Activators (antecedent conditions that direct behavior), behaviors, and consequences (events that follow and motivate behaviors and influence attitudes) are easiest to define, measure, and manage.

Source: The Psychology of Safety, Geller, 2001