In memory of James Reason, I thought it would be fitting to share, in my professional opinion, one of the greatest safety models of my career. If businesses could just embrace this model when it comes to how they investigate events, we could move workplace safety forward a couple of decades. The model is quite simple and has proven to make sense of people’s errors, mistakes, and violations. I am NOT saying it is perfect, but it is about as close to making sense of our failures as any model available today. We should recognize the fact this model was formulated by Reason 25 years ago and has stood the test of time. And yes there are plenty of naysayers from the academic world, but I doubt that many practicing safety professionals who have used this model would find much to disagree with.

In memory of James Reason, I thought it would be fitting to share, in my professional opinion, one of the greatest safety models of my career. If businesses could just embrace this model when it comes to how they investigate events, we could move workplace safety forward a couple of decades. The model is quite simple and has proven to make sense of people’s errors, mistakes, and violations. I am NOT saying it is perfect, but it is about as close to making sense of our failures as any model available today. We should recognize the fact this model was formulated by Reason 25 years ago and has stood the test of time. And yes there are plenty of naysayers from the academic world, but I doubt that many practicing safety professionals who have used this model would find much to disagree with.

Here is Mr. Reason in his own words explaining: Active and Latent Failures, Errors, Mistakes, and Violations from his book “Organizational Accidents Revisited” (2016).

NOTE: Mr Reason was from England so some spelling of words may be different than the USA English spelling. Out of respect, I have left the spelling as is from his book.

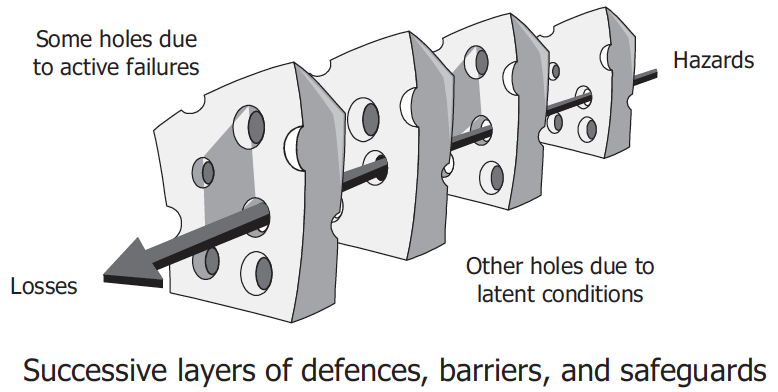

“Despite their huge diversity, each organizational accident has at least three common features: hazards, failed defences and losses (damage to people, assets and the environment). Of these, the most promising for effective prevention are the failed defences. Defence, barriers, safeguards and controls exist at many levels of the system and take a large variety of forms. But each defence serves one or more of the following functions:

• to create understanding and awareness of the local hazards;

• to give guidance on how to operate safely;

• to provide alarms and warnings when danger is imminent;

• to interpose barriers between the hazards and the potential losses;

• to restore the system to a safe state after an event;

• to contain and eliminate the hazards should they escape the barriers and controls;

• to provide the means of escape and rescue should the defences fail catastrophically.

These ‘defences-in-depth’ make complex technological systems, such as nuclear power plants and transport systems, largely proof against single failures, either human or technical. But no defence is perfect. Each one contains weaknesses, flaws and gaps, or is liable to absences. Bad events happen when these holes or weaknesses ‘line up’ to permit a trajectory of accident opportunity to bring hazards into damaging contact with people and/or assets. This

concatenation of failures is represented diagrammatically by the Swiss cheese model (Figure 1.1) – to be reconsidered later.

The gaps in the defences arise for two reasons – active failures and latent conditions – occurring either singly or in diabolical combinations. They are devilish because in some cases the trajectory of accident liability need only exist for a very short time, sometimes only a few seconds:

Active failures: these are unsafe acts – errors and/or procedural violations – on the part of those in direct contact with the system (‘sharp-enders’). They can create weaknesses in or among the protective layers.

Latent conditions: in earlier versions of the Swiss cheese model (SCM), these gaps were attributed to latent failures. But there need be no failure involved, though there often is. A condition is not necessarily a cause, but something whose presence is necessary for a cause to have an effect – like oxygen is a necessary condition for fire, though an ignition source is the direct cause.

Designers, builders, maintainers and managers unwittingly seed latent conditions into the system. These arise because it is impossible to foresee all possible event scenarios. Latent conditions act like resident pathogens that combine with local triggers to open up an event trajectory through the defences so that hazards come into harmful contact with people, assets or the environment. In order for this to happen, there needs to be a lining-up of the gaps and weaknesses creating a clear path through the defences. Such line-ups are a defining feature of orgax in which the contributing factors arise at many levels of the system – the workplace, the organization and the regulatory

environment – and subsequently combine in often unforeseen and unforeseeable ways to allow the occurrence of an adverse

event. In well-defended systems, such as commercial aircraft and nuclear power plants, such concatenations are very rare. This is not always the case in healthcare, where those in direct contact with patients are the last people to be able to thwart an accident sequence.

Latent conditions possess two important properties: first, their effects are usually longer lasting than those created by active failures; and, second, they are present within the system prior to an adverse event and can – in theory at least – be detected and repaired before they cause harm. As such, they represent a suitable target for safety management. But prior detection is no easy thing because it is very difficult to foresee all the subtle ways in which latent conditions can combine to produce an accident.

It is very rare for unsafe acts alone to cause such an accident – where this appears to be the case, there is almost always a systemic causal history.”